The WPA-inspired, living wage program for artists offering much needed stability and support

Artists at Work is a workforce resilience program that has provided a salary and benefits to dozens of artists across the U.S. It’s part of a burgeoning movement to value and pay artists fairly.

How do artists in the Delta region make a living from their art?

“We can’t,” says Lisa Hicks-Gilbert, a poet, activist, and mayor of Elaine, Arkansas. “You’re not going to make a living.” Support and resources for artists in the deep South, particularly those in rural areas are scarce. And although social media has made it easier to build a community and sell work, access to affordable and quality internet is yet an additional hurdle for those in ultra-small communities, like Elaine, which has a population of less than 1,000.

Hicks-Gilbert found an unusual source of support through Artists at Work, a workforce resilience program that employs artists to work with a social impact organization and focus on their artistic practice for a year. From 2022 to 2023, Hicks-Gilbert worked with a local community center and received a salary, health benefits, and professional development opportunities.

With the freedom and time to focus on her art practice, Hicks-Gilbert developed a multimedia exhibit about the 1919 Elaine massacre, one of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history.

“I can just imagine the stress I had trying to do this work, and then the additional stress trying to work another job,” Hicks-Gilbert says. “I just don’t know how I would have been able to do it.”

Artists at Work is part of a burgeoning movement in recent years to pay artists fairly. The devastation of the pandemic combined with the murder of George Floyd in 2020 sparked a reckoning across the arts ecosystem, with artists demanding pay transparency, equity for artists of color, and a rehaul of how the arts are funded.

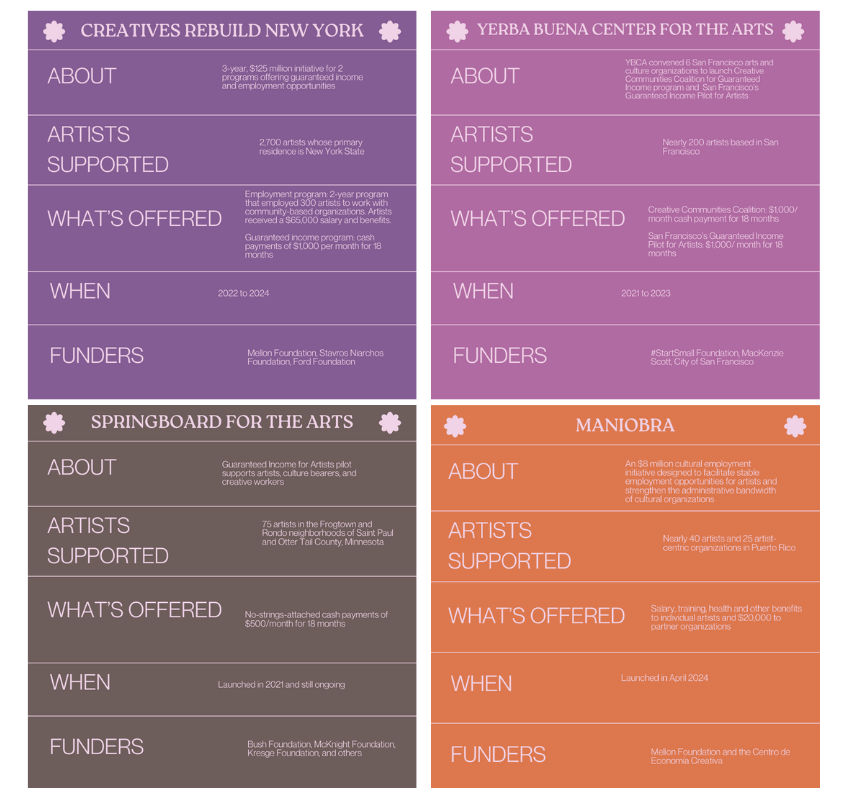

One way this reckoning has manifested is in programs that hire artists to support their practice, including Creatives Rebuild New York, a 3-year, $125 million initiative which employed artists for two years to work with a community-based organization, offering a $65,000 salary and benefits. Creatives Rebuild New York also included a no-strings-attached, cash disbursement program for 2,400 artists.

Other guaranteed income programs like Springboard for the Arts Guaranteed Income for Artists program, which offers 75 Minnesota-based artists $500 per month for 18 months, and San Francisco’s Guaranteed Income Pilot for Artists, which dispersed $1,000 per month for 18 months to 130 artists, have provided regular cash payments with no strings attached.

When Hicks-Gilbert was offered the Artists at Work position, she initially planned to write a book of poems, short stories, and prayers about the Elaine massacre. Her plans shifted after she came across letters from a military officer who described atrocities of the massacre, where hundreds of Black Elaine citizens were killed. The letters inspired Hicks-Gilbert to pivot and develop an exhibition called “Silent No More,” centering the stories of victims, survivors, and descendants.

The process of creating an exhibit was all consuming and stressful at times. Encouragement from community partners through AAW was crucial. “Having the time, the people there to support you, especially in small rural areas like this, because I could not see what I was doing as art. I couldn’t see myself as an artist because all I saw myself was, was a community organizer,” she says.

The exhibit opened in September 2022 and Hicks-Gilbert is currently expanding it into a touring work. While employed through AAW, she also ran for mayor to improve infrastructure issues in Elaine, eventually becoming the first Black and first elected female mayor in December 2022.

Artists at Work, an initiative of the Office performing arts + film, is inspired by efforts like the Works Progress Administration, a Depression-era relief program that offered millions of jobs as Americans struggled with widespread poverty and unemployment. Part of the WPA included the Federal Art Project, which employed more than 10,000 artists to create works of art across the U.S.

More than 80 years later, another crisis — the pandemic — instantly decimated the livelihoods of many artists. “We really wanted to do something about it and take what was obviously a devastating moment and turn it into an opportunity for change,” says Nadine Goellner, AAW managing director.

Artists at Work founding director, Rachel Chanoff, raised seed money to launch a pilot program in Western Massachusetts, pairing artists with organizations in the area including Jacob’s Pillow and the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

In July 2020, six artists were hired through the pilot which initially included a $15,000 stipend and benefits for six months — “to do two things: one, to keep up their practice as an artist, because we value that and they should be paid for that,” Goellner says. “And also for them to lend their creative skills and artistic vision to the mission of a local, social-impact initiative.”

As part of the pilot cohort, Joe Aidonidis, a filmmaker who runs a production company in the Northern Berkshires, worked on a documentary about addiction and recovery. He juggled running his company with the AAW program which allowed him to spend time on passion work which doesn’t always come with a “financial reward.”

“It’s such a bizarre thing of, here’s your living wage, just go be an artist in the world,” Aidonidis says. "We had the flexibility to just see where it takes us and that was so unique.”

A $3 million grant from the Mellon Foundation in 2021 allowed Artists at Work to expand the program across the country over a three-year period, increasing the salary to about $32,500, adding benefits, and offering project funds. Additionally, AAW offered participation fees to partner organizations to help build capacity and compensate for staff time dedicated to program-related work.

Artists are hired to work 30 hours a week and spend about a third of their time working with a local partner organization and two-thirds of their time on their own creative practice.

Although artists clock their hours, what counts as “work” is very loose.

“We try to be really nimble and open,” Goellner says. “If you've spent time thinking about your practice today, that is work. That's creative work, and those are hours logged.”

Since its 2020 launch, AAW has offered a salary and benefits to 70 artists and culture workers across 11 states, and received additional funding from regional and community foundations. More than 80% of artists hired through the program are artists of color.

“We’re trying to develop those skills so that artists are set up to see the value of what they do and be able to take that into different arenas after the program ends,” Goellner says.

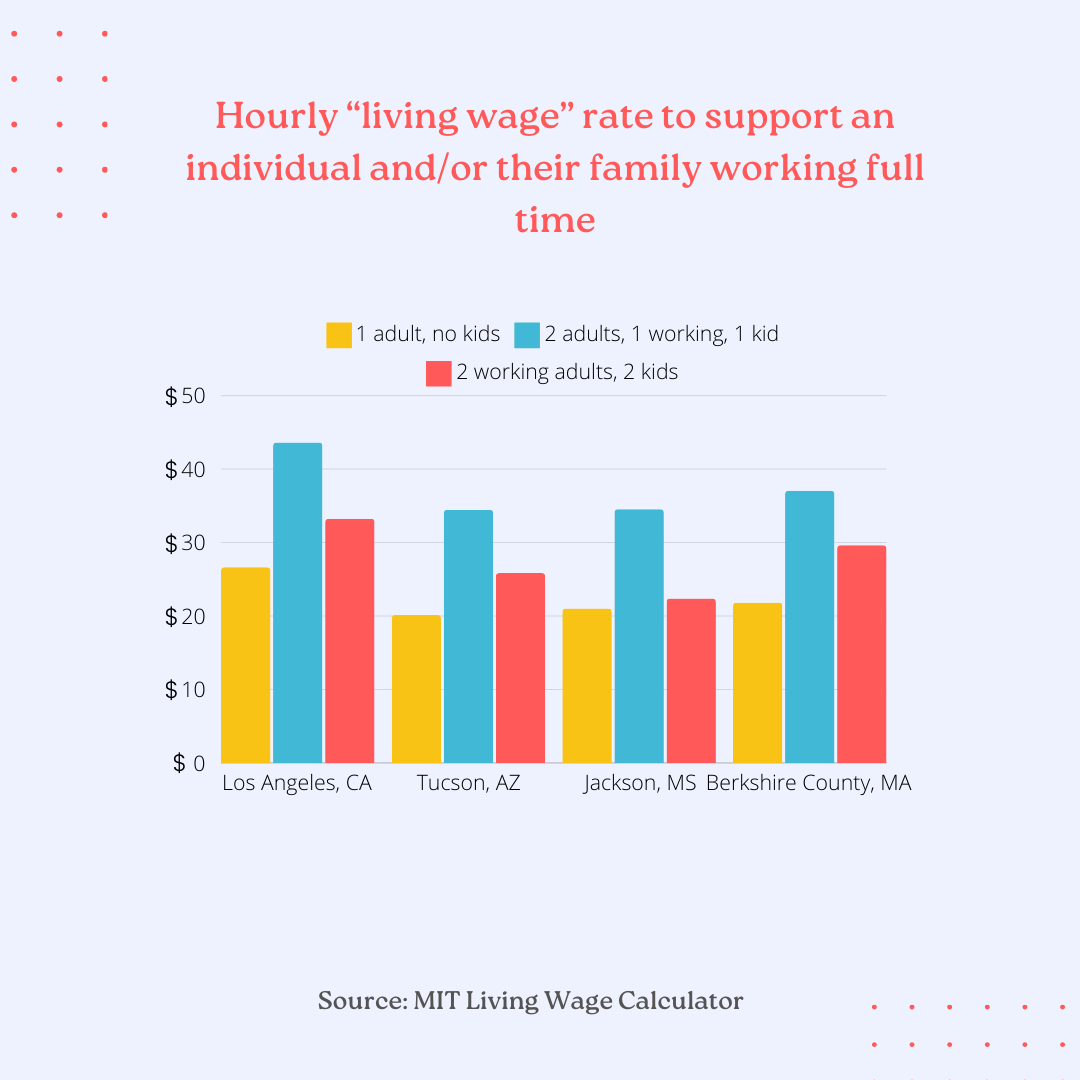

To determine salaries for the program, AAW referenced MIT’s Living Wage Calculator, a tool that helps employers estimate a full-time wage that covers basic living expenses across the U.S. Under the Mellon Foundation funding, artists made around $32,500, with the exact salary varying by region.

But as the cost of living continues to rise, what counts as a living wage?

According to the MIT Living Wage Calculator, an income that allows someone to live comfortably changes from state to state.

In Los Angeles County, for a single adult with no children, the calculator estimates a living wage as $26.63 an hour, and for a household with two working adults and two children, a living wage increases to $33.24 an hour. In Jackson, Mississippi, for a single adult with no children, the living wage is estimated at $21.02 an hour, and for two working adults with two children, it’s $22.39 an hour.

Artists at Work groups its cohorts by region. 15 artists were part of AAW’s Borderlands cohort, which included Arizona, New Mexico, Southern California, and Texas. Other cohorts include the Mississippi Delta region, and Los Angeles County, among others. The organization took a regional approach to setting salaries — the Borderlands cohort received $32,500 and those in Los Angeles County received slightly more because of the state’s labor laws, Goellner says.

“I'll just be very frank, we are in conversation with ourselves about [how] to still maintain equity and hit the standards that we need to be compliant and honor the work of the artists in the right way,” Goellner says. “It’s something that we are wrestling with. In the beginning, when we started in the pandemic, artists weren't working at all.”

Goellner acknowledges that the fellowship isn’t a one-stop-shop when it comes to pay, and says that many artists kept part time jobs to sustain their livelihoods, something echoed by Aidonidis and recent alums.

Jason Chu, an LA-based rapper whose work tackles culture and heritage, had been making a living wage since 2017 from a mix of music, touring, consulting, and other projects centering art.

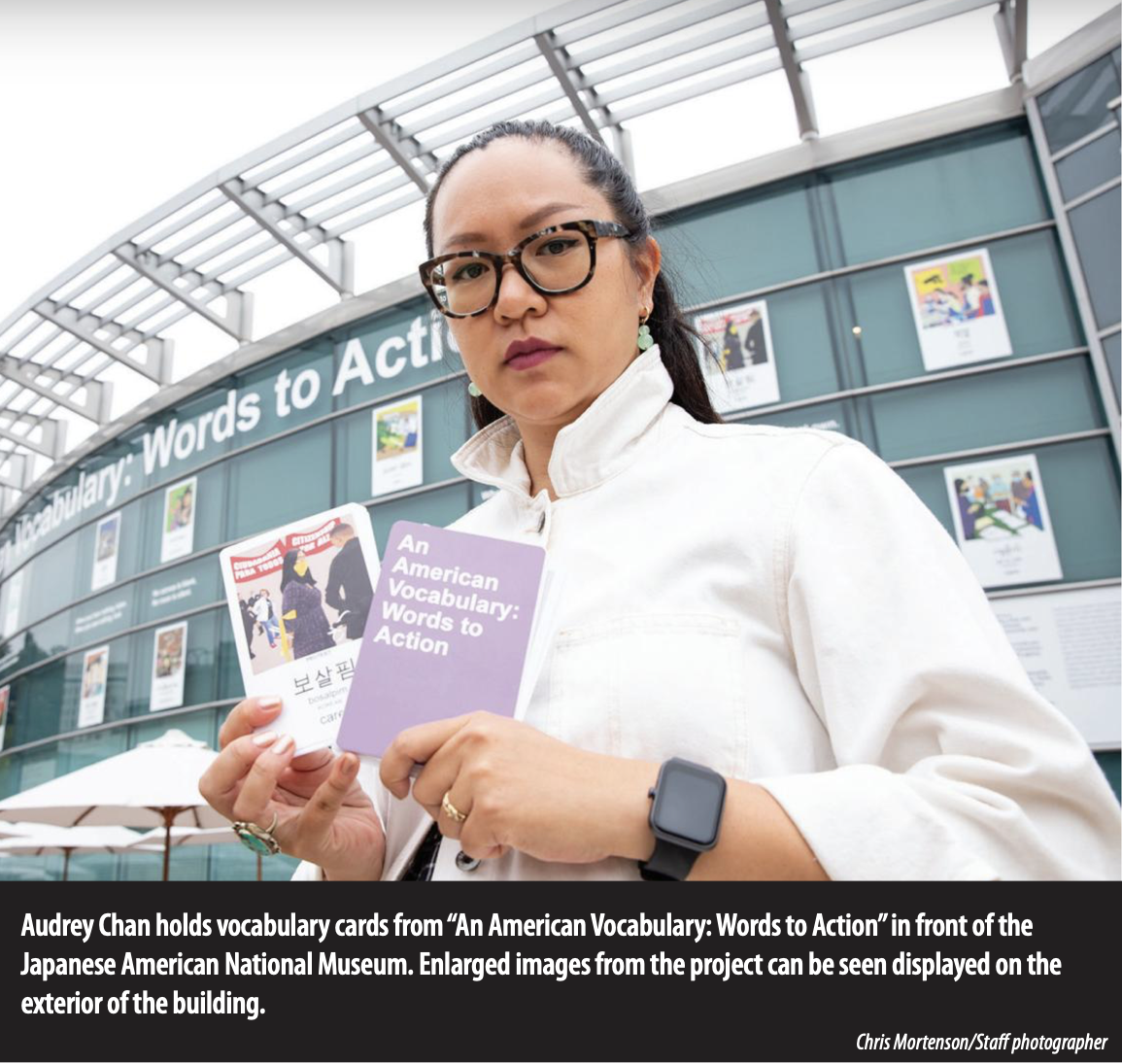

As an AAW artist from 2021 to 2022, Chu partnered with LA visual artist Audrey Chan to create work with the Japanese American National Museum. Their collaborative project, “An American Vocabulary: Words to Action,” is a set of multilingual flashcards portraying figures, events, and practices, that also honors the rich and complex linguistic traditions of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.

While participating in Artists at Work, Chu kept other freelance gigs and also worked on a new album. The biggest benefit of being an AAW artist was a year of stability, “knowing where my benefits are coming from, knowing that I have a base income every month,” he says. “My mental health was great in 2022.”

Chan was familiar with the Artists at Work model, as the inaugural artist-in-residence at the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, which included a $15,000 honorarium. She found the AAW application on social media and as an artist whose work is rooted in community, applying was a “no brainer,” she says.

Chan was also pregnant when she applied and had recently taken on a mortgage with her husband. “I had the need for a predictable or stable income — it was top of mind more than ever before,” she says.

For many artists, financial stability affects “whether or not they even feel they can have kids or not,” Chan says. “In terms of how much risk do you take on to build this career that — structurally, American society doesn't really support this work financially in the way it should.”

Running Artists at Work requires balancing the creative with the realities of managing an employment-based program. Navigating labor laws, and the high cost and complexities of healthcare in the U.S. has been “humbling,” Goellner says.

“We've had to do all the other kind of compliance things like host anti-sexual harassment, anti-bias trainings, all the things that you do as an employer and factor those in as well,” she adds.

Despite its challenges, over nearly four years of the program, artists have reported deep satisfaction, according to a recent impact report. The survey indicates that 88% of AAW alums secured post-program, paid opportunities, and 81% said they found expanded or improved networking opportunities.

For Chu, one highlight from the program was the opportunity to collaborate with the Japanese American National Museum. “Having the co-sign of a credible, recognizable institution within my community, that has meant a lot in terms of my credibility as an artist,” he says.

This March, AAW launched two new artist cohorts in Indianapolis and North Adams, Massachusetts. The program also set a standard salary for all current cohorts — $35,570 with an additional $5,000 in project funds. Over the past year, AAW signed up with a professional employer organization which allows artists to contribute to a 401K.

To ensure the program’s sustainability, staff are thinking about the importance of private-public partnerships.

“We're really trying to have a lot of conversations with public sector folks, representatives at various levels of government to figure out how we can match this leadership in private philanthropy with public support as well,” Goellner says. “We know that's a long game to enact real policy change.”

Goellner sees Artists at Work as part of a larger shift of recognizing the importance of the arts and artists as essential pieces of our democracy and paying them fairly so they can live full lives.

“Creative thinking is not just a hobby,” she says. “It needs to be valued as this essential skill, and this essential part of a healthy society.”