How artist Basil Kincaid made their most ambitious and transformative work yet

With little institutional support for the arts in St. Louis, Basil had to create their own opportunities to break into the art world establishment

This interview was originally published in September 2022.

Basil Kincaid, a St. Louis, Missouri, and Accra, Ghana-based artist who describes their artistic practice as a spiritual pursuit.

Through work that spans quilting, sculpture, collage, photography, and performance, Basil often celebrates the power of the Black family and honors sacred, ancestral art traditions across the diaspora.

“I’ve always situated my practice from a more emotional and spiritual context than the standardized conceptual context of the Western canon,” Basil says. “I’ve always felt like art, especially for Black and Indigenous people, was more than about recognition of your name. It was connecting us to something higher, and connecting us to the deeper truth within ourself and connecting us to each other.”

Keep reading to learn how the 35-year-old carved out their own lane to make profound art with little institutional support in the early stages of their career. In recent years, Basil has received national and international acclaim for their work, recently opening their first solo show in New York in September.

A transcendent dream guided Basil to quilting. It was 2016, and Basil was living with their godbrother and godsister in St. Louis.

Basil dreamed of their grandmother, their father’s mother, standing in front of a row house in St. Louis. “The whole house was wrapped in a quilt and it was like waves of this golden aura washing out of her,” they recall. “As I walked into the waves of this radiance, each wave hit me more and more powerfully.”

Waking up, Basil immediately realized, “that’s it — I’m supposed to be making quilts.”

At the time, Basil didn’t know how to sew, but they would find a way to learn. “God gave me a vision, you couldn’t tell me anything at that point.”

With a used sewing machine from Facebook and old kids’ clothes from their godbrother and godsister, Basil found that sewing came naturally. “It felt like ‘Angels in the Outfield,’ like my grandma was with me the whole time. That was such a comforting sensation.”

About six years later, Basil’s quilts are being showcased in their first New York solo exhibition, “River, Frog, and Crescent Moon,” at Venus Over Manhattan gallery. The show features a series of large-scale quilted, embroidered, and sculpted works made primarily with found or donated objects.

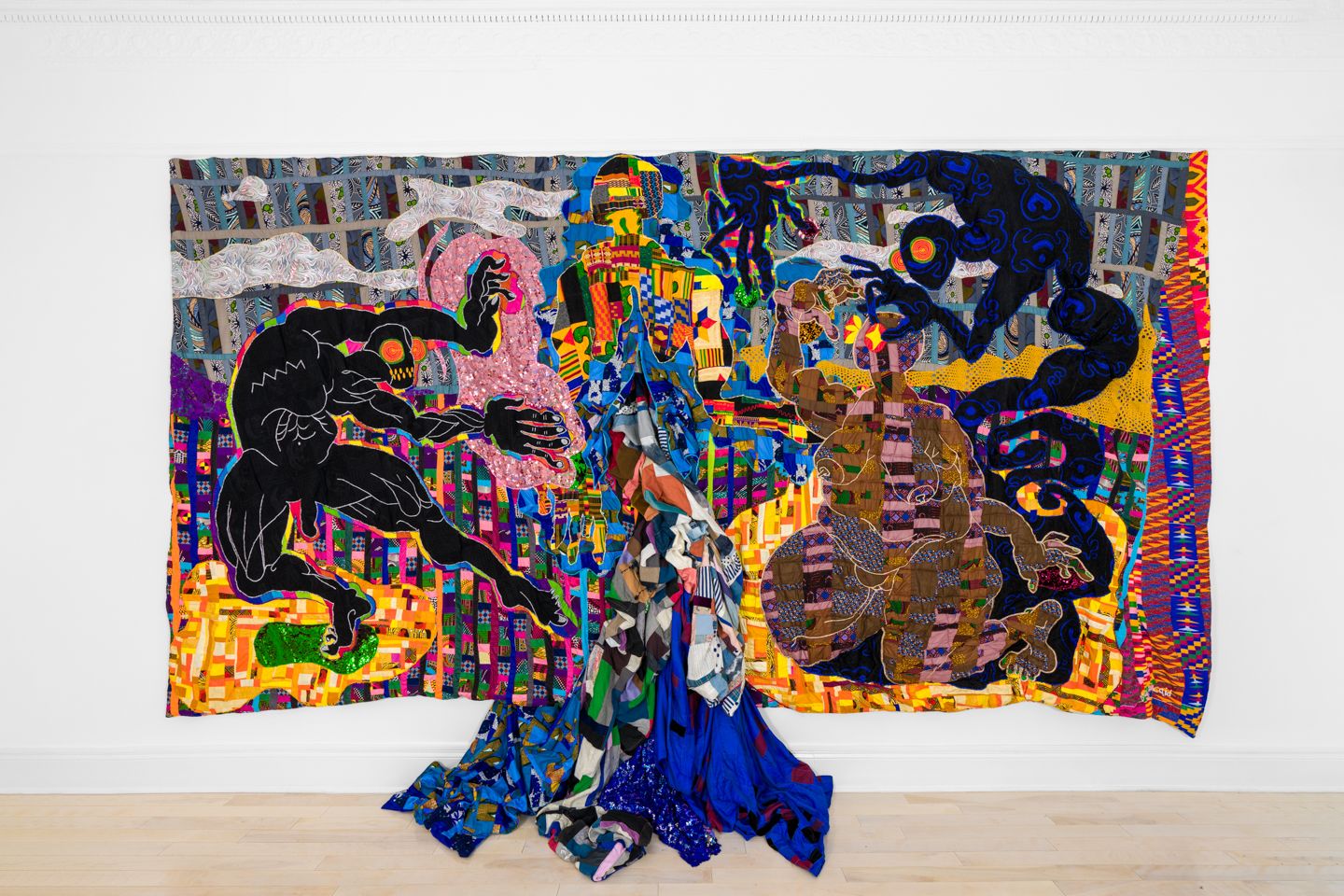

One of the quilts in the show, “The River,” made between 2017 and 2022, represents a major turning point in Basil’s work and mindset. The giant, three-dimensional, multi-layered quilt, measuring approximately 9 feet by 17 feet, explodes in color. Among the intricate geometric patterns, nude figures immediately pull focus. A chiseled black figure, a Rubenesque brown figure, a spiraling black and blue figure with large hands and orb-like eyes direct energy toward the center of the quilt, a river that drapes outward and down onto the floor.

The work helps to tell the story of Basil’s journey. Basil calls it their first true masterpiece.

“The River” began with frustration from being overlooked by the art world. And so Basil decided, “I’m about to make the best piece I’ve ever made in my life.”

The quilt incorporates techniques Basil honed throughout their development as an artist. Comprised of materials Basil began collecting in 2017, the fabric that flows onto the floor uses pieces of Basil’s first-ever quilt. ”The river started feeling like the DNA, the path, everything passed down bit by bit. All this genetic information synthesizing to form me,” they say through tears.

After seeing the work installed in New York, Basil returned to their hotel room and wept. “I look at that — I didn’t even do this, God did this. I’m just hands. That’s why a lot of time in the work you’ll see these glowing orbs in the hands. You just have to sometimes let yourself be hands, let the spirit move through you.”

Basil began drawing at three years old, filling an entire page with tiny, contiguous circles. During summers with their parents, grandparents, and brother at a family farm in Arkansas, Basil’s creativity flourished.

“Ambient things that I didn’t even realize were going to end up becoming such a pillar of my practice, like watching my grandmother do her needlepoint and quilting and just watching [my grandparents’ and parents’] relationship,” Basil says.

“They love the hell out of each other and that was such a special thing to observe. That’s what has given me such a foundation — with a loving family structure, it pushes a lot of the excess to the side and made it where my brother and I can really focus on our gifts with a sense of security that I feel like a lot of other people don’t have.”

As a student at Colorado College, Basil studied drawing and painting. But as the only Black student in their department, Basil also felt alienated and a sense of separation from the art world in the Western canon.

After graduating in 2010, Basil made it a goal to study Black art and connect with other young Black artists. They began thinking more about material and place and surroundings, which “was when I started collecting materials, basically foraging, doing this found-object work.”

In 2014, Basil was awarded a residency with Arts Connect International, which gave them support to travel, collaborate with local artists, and create new work in Accra. In an effort to encourage dialogue around technological advancements and the often devastating impact on the planet, Basil worked with children in the neighborhood to collect discarded pre-paid calling cards from the streets. The materials were then woven into collages and later exhibited at the Luminary gallery in St. Louis.

After returning to St. Louis at the end of 2015, Basil sold their first five-figure art piece. But it would still take a few more years to receive widespread recognition.

In 2016, as Basil was learning to quilt, they also juggled selling collages on Facebook and working in a data entry position for the National MS Society. “I’m doing this data entry job, living with my godbrother and godsister and making quilts in the basement outside of work,” Basil recalls.

“Then they decided they were gonna move to Atlanta, so I had a real decision to make because this free housing, I’m not about to have it anymore. Do I get an apartment or an art studio, because I couldn’t afford both.”

Basil chose to rent the art studio for $250 a month. With a shower (but no kitchen), Basil was able to squat there. “I told myself, imma hustle my way out of this room.”

Basil sold collage prints during breaks at work. At a certain point, the collages began bringing in more money than the data entry job. Basil was considered for a promotion, but their boss, a Black woman, encouraged them to move on and pursue art full-time.

“I decided I’m going to do 4 hours a day making and selling these collages. And I’m going to do 8 hours of making these quilts, and I’m going to use the collages to fund my quilt pursuit.”

Basil also figured out how to use Instagram to hack the art world establishment.

They painted a white wall to resemble a gallery space and photographed their work, making it appear as though they were already successful. Posting the quilts on Instagram worked. “People started becoming interested,” Basil says. As part of the grind, Basil used Facebook, pop-up events, even a few barber shops, to sell prints. While delivering art, they also collected donated materials and their backstories for quilts.

“Back then, I didn’t really sleep as much. I’d be sewing until about midnight, sleep, wake up four or five, and get back to the cycle of hustling, because I was just so frustrated. I felt like I was making really great work and everyday people supported it, but there was no institutional support in St. Louis.”

“Those L.A. artists, New York artists, Chicago, there’s infrastructure where if you’re really doing it in the art, there’s places that will give you opportunities. In St. Louis, we had to make up all our own opportunities.”

For Basil, creating opportunities meant organizing street performances, installing quilts in vacant lots, renting store fronts, and staging openings of their work, documenting it “like it was a real thing.”

Basil reached out to galleries to show their work, and began connecting with Black art collectors. “I would pack everything up in my car, drive out to these universities, do the show, do the talk, drive back just on a break, just to be building up my resume.

Basil found community with other local, emerging artists including filmmaker Damon Davis and painter-sculptor Kennedy Yanko, sharing resources, and nominating each other for opportunities.

2018 was a breakout year.

JPMorgan Chase acquired some of Basil’s work for the company's permanent collection. Basil began doing more group and solo exhibitions in Missouri, across the U.S., and abroad.

Basil also began exercising again, taking care of their mental health, and getting more sleep.

2020 brought an explosion in print sales.

Basil used the money to build a studio in Tema, Ghana called the Laboratory. Ghana is where Basil now makes most of their work and spends about 60% of their time. “I just wanted to be a positive force in that area,” they say.

Partnering with their friend in Ghana, Rhodaline, Basil hired community members to work in the studio and help make quilts. Incorporating local art traditions like Ghanaian embroidery is important. As a generational quilter, Basil prioritizes keeping “traditional art forms alive and then amplifying them to meet contemporary needs and contemporary questions.”

The studio is a reflection of the values Basil’s parents instilled in them: “wherever you go, add value to that space.”

Basil’s advice for artists working in communities with little institutional support

Discipline and tenacity, you’ve got to develop those. When you come from a place that's not in the spotlight, it's a unique opportunity. Because yes, there's the struggle of not being seen, but at the same time, there's a different level of freedom when you're not under scrutiny. I used reproductions as a way to buy myself some freedom to focus on the larger practice. There's a lot of tools out there now that make monetizing your work way easier than ever before. We're in a unique time here where in some ways, it's kind of easier than ever before, but there's also a lot more noise.

If this is really what you want, and you feel called to do it, my main advice is don't try to be an artist just because you think it looks sweet.

If you're not really called to do this, let it be a hobby, because it's great to make art. Everybody should have some creative outlet. But if you want this to be a profession, you really have to go all in. Me, my friends that have gotten any kind of access, we worked tooth and nail. Get up, exercise, eat, go to the studio, stay in the studio with the phone off. The core of being an artist is observation and if you're really observant, you'll notice entry points.

And you have to put yourself out there. The social side is the hardest side for me. But if you go to the openings and talk to people, introduce yourself, meet people and be authentic, people can tell when you're trying to just sell. For you to be true to this, you have to be willing to do it with no outcome. Don't think about, oh this person is wearing Gucci shoes, I one day want to be wearing Gucci shoes. Don't think about any of that stuff. For me, it's always been a competition with myself. I'm always reaching to evolve and reflect and be better than I was the day before. More focused than I was the day before. More emotionally tender than I was the day before.

If you do those things, the game weeds itself out. To me, the people that don't quit are the ones that stick around. Some people get noticed in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s. None of that really matters. The goal should be becoming the most true version of yourself.

I think art is a tool to understand yourself, first, and to understand the world around you first. The market is second. That was why I sold collages, because with the collages, I could allow myself to think monetarily and business-minded around it. But there has to be some art that's just entirely free. And eventually people will want that stuff and pay for it. But that was all ancillary effects. If you asked me what I wanted to be as a kid, I didn't know, I just knew I wanted to draw every day. I didn't know you could be an artist. So I think that's a good mindset. Just be focused on your gift and not on the outcome.