How Chicago’s DanceChance is reimagining the artist grant

DanceChance offers choreographers the opportunity to win $4,500 via random draw. It’s part of a movement to democratize arts funding.

As an independent journalist, applying to grants feel necessary for survival, even though the process is draining and often discouraging. In talking to artists over the years, I've heard much of the same.

But what if there were another way?

The pandemic cast a harsh light on the exploitative nature of the arts ecosystem, including arts and culture philanthropy. In recent years, artists have pushed philanthropists to consider alternatives to traditional grantmaking, which often involves a lengthy application and obscure selection process, to move money more quickly to the people who need it most.

Earlier this year, I came across an Instagram post about a lottery-based grant in Chicago called DanceChance. Organized by the Chicago Dancemakers Forum, the bi-monthly gathering is both a showcase of local choreographers and an opportunity for anyone in the audience to enter a drawing for $4,500 to fund their work and present at the next event.

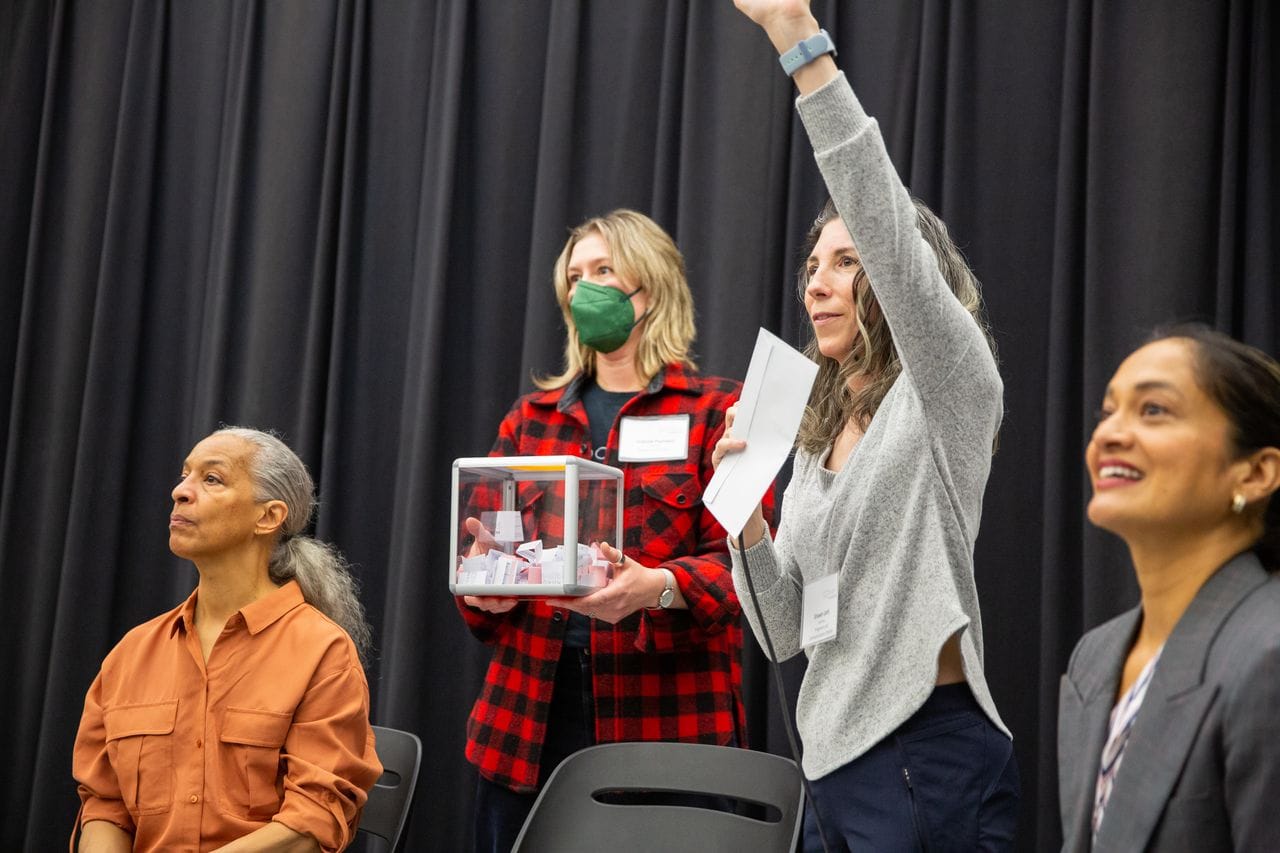

On a warm evening in May, I took the Blue Line to the third installment of DanceChance this year at the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities. Entering the space felt like stumbling into a fluorescent-lit party. I was warmly greeted by the event organizers and encouraged to enter the drawing, which meant filling out a slip of paper with my contact info and dropping it into a small, clear box before performances from previous winners began.

Chicago Dancemakers Forum executive director, Joanna Furnans, kicked off the event with an overview.

DanceChance has a 15-year legacy, created by DanceWorks Chicago and conceptualized as an open-mic night for dance, where artists were chosen at random to show and discuss their work in an informal setting. Near the end of 2022, DanceWorks passed the torch to Chicago Dancemakers Forum, an organization that has supported local dance artists for 20 years.

As new custodians of the program, Chicago Dancemakers took the opportunity to redesign it.

The revamped DanceChance launched with a few key changes including offering selected artists a $100 honorarium, providing video documentation of the performance to choreographers, and moving throughout the city to different locations to attract new artists.

But Joanna, who is also a dance artist, knew that DanceChance choreographers needed much more monetary support. “Any lead artist wants to pay their collaborators a fair wage, they just never have the funds to be able to do it,” she told me later by phone. “We as a dance service organization, or even as a sector, can’t continue to talk about pay equity without showing up with the funds to allow people to be able to exercise it.”

In 2023, Joanna applied for additional funding and with support from the City of Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events and the National Endowment for the Arts, DanceChance increased its artist honorarium from $100 to $4,500.

The fully-funded DanceChance launched in January. After being selected through the lottery draw, artists receive $3,500 and six weeks to create up to 10 minutes of a dance work-in-progress to share at the next DanceChance event. They receive the remaining $1,000 after the performance as seed money to continue their work.

According to participant survey data, choreographers have used these funds for musical composition, rehearsal space, costumes, transportation, taxes, and saving for the future. “Most of the funds have gone to dancers, who have been paid $15 to 33 an hour for rehearsals and an average of $100 for the DanceChance performance,” wrote Shawn Lent, programs and communication director for Chicago Dancemakers, in an email.

At the May DanceChance, there were about 50 people in the audience. We watched performances from Tanya Armendariz, who presented a waving-style piece with three other dancers and Jonathan St. Clair, aka “InLight,” who performed a solo showcase of a few different hip-hop styles including breaking and popping. I noticed that the crowd was unusually diverse for a dance show, a mix of ages and races, and different styles of dancers — an observation confirmed by demographic data the organization collects from its events.

To me, one of the most fascinating aspects of DanceChance is that anyone can win $4,500 — it doesn’t matter if you’ve been choreographing for six months or 60 years. There are no judging panels who decide which artists are “good enough.” Because so many funding opportunities rely on this idea of merit — outside markers, previous accolades, along with the subjective nature of worthiness — this model feels really novel.

I asked Joanna if she received any pushback for the concept.

“What’s the worst that’s going to happen,” she said. “People in need show up and get the money. Ideally, these are artists. I just trust artists, that’s the bottom line. You have something you want to explore. You’re calling yourself a dancer or dance maker. Great, go for it. See what happens. I don’t want to be in the business of allocating resources all to people who are ‘the best.’ I want to be in the business of supporting with resources an ecosystem, a culture of people who are creative — period.”

“I can’t guarantee the resources that get handed out are always going to create some sort of best-in-show performance,” she continued. “That’s not the negotiation we’re working with here. It’s really like how are we fueling an entire society or culture that values the creative process?”

In a movement for equity and justice ignited by the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd, a rise in mutual aid, there has been even more scrutiny on philanthropy and the grant making process.

“There’s been an increased interest in grantmakers actually making that commitment to not just moving money, but changing their relationship to how they move money or how they steward money,” says Sruti Suryanarayanan, a researcher and organizer with Art.coop, a resource for artists who are interested and involved in the solidarity economy.

One of Sruti’s research interests is non-hierarchical giving, which includes general operating grants and unrestricted funds for individual artists, to shift “power away from grantmakers to grantees who have historically just been excluded from power.”

Real world examples include the Cultural Solidarity Fund, a coalition of arts and culture organizations in NYC that banded together to give $500 relief microgrants to over 2,000 artists since 2021. The Map Fund’s microgrant initiative is inspired by artist-led mutual aid networks and allowed previous grant winners from 2022 to select an artist in their community to receive an unrestricted $1,000 grant. Another is the City of Chicago’s Creative Worker Assistance Program from 2021 which provided around 450 relief grants via lottery system to low and moderate income artists who lost wages from Covid.

“What non-hierarchical grant making does is that it takes away the expectation that grantees have to define their worth or fight to receive the money they need,” Sruti said.

Sruti emphasized that democratized forms of giving are not new. “They’re actually ancestral ways of being in relationship with one another,” they said, sharing an example of a money pool their family participated in.

“These go back to things that my parents practiced in their home countries. It's not the only model, there have been models of people coming together to collectively govern their resources for centuries. And right now because of how deep a toll capitalism has taken on us, I think we’re finally remembering the things that we knew were true and trying to incorporate them wherever we can.”

Currently, Joanna is searching for funding to continue offering $4,500 grants to choreographers next year. Chicago Dancemakers Forum also offers another grant that provides $25,000 to a small group of artists each year, but the bar for entry is much higher. Artists fill out an application and submit work samples which are reviewed by a panel of judges.

In 2022, the organization introduced a lottery-element to the process.

Once the judges narrow applications to its finalists, grant winners are selected by a random draw.

“When you get down to 10 finalists that you’re thinking about, the decisions that get made in that room, usually that’s where a lot of the bias shows up, where people are just like, ‘well, I like this work better than that work,’" Joanna said. "It really gets into a dicey conversation, when in reality all 10 finalists are equally ready, capable, excellent candidates for the program."

At the May DanceChance, after the performances and brief artist Q&As, there were a few minutes for community announcements, where anyone in the audience could share upcoming performances or auditions.

Joanna envisions building a community, “a place where dance artists from around the city who work in different styles know that they can count on DanceChance as a place to show up and see work, have the potential to get some funding, but also to network with each other.”

“It’s rare that there’s a space where dance communities, all different styles — folks know that they can come to it and it feels safe, it feels inclusive, and it feels generative to actually show up and get to know each other.”

Finally, the moment arrived to draw three names for the next round of funding and performances. Someone brought out the clear box with entries, including my own. I put my name in because I’ve recently had the urge to choreograph. As we sat in anticipation for the drawing, I was cautiously hopeful but excited for whoever won.

Spoiler — my name was not drawn, but I’m definitely interested in giving it another shot.

Are you a Chicago dance artist in search of funding? The next DanceChance is scheduled for September 9 from 6:30 to 8 pm in at Loyola Park.