Digging through an anarchy collection: Radical art over time

The Labadie Collection at UM is one of the oldest collections of items related to anarchism, labor, and other movements. I spent time with the collection’s art related materials.

The Labadie Collection at UM is one of the oldest collections of items related to anarchism, labor, and other movements. I spent time with the collection’s art related materials.

Finding connections between art activism of the past and today

By Makeda Easter

December has always been my favorite month. Growing up in the South, December would often bring a surprise burst of cool — maybe even cold — weather. As a bookworm with a rich inner life, I loved the shorter, more dreary days. And I’ve always been into the magic of Christmastime — the lights, ice skating at the Galleria mall, making my wishlist for Santa, the numerous movies (including my all-time favorite, Jim Carrey’s Grinch). There was also the anticipation of my birthday, sandwiched between Christmas and New Year’s Eve.

As an adult, the magic of Christmas has sadly faded quite a bit. And now living in Michigan, I’m really, really missing the sun and its warmth. But in recent years, I’ve been excited for something I took for granted in childhood. As December comes to a close, the treadmill of life seems to dial down a few notches, forcing much needed reflection and time with family and loved ones.

I don’t feel so guilty about taking my time responding to an email. I saw an Instagram post that said something like, embrace melting into the couch.

One arts nonprofit in Chicago, Sixty Inches from Center, announced on December 1 that the entire organization was slowing down through the end of January:

“Without pausing our pay, we will be redirecting the time we would usually spend on Sixty things to our individual creative practices, loves, nourishments, processes of reflection, and future musing as we transition into 2023.”

More of this please.

Rest is not just a luxury, it’s a necessity. I hope you all get some time for rest and rejuvenation.

subscribe to the art rebellion newsletterArts and anarchy (and many other social movements)

United Farm Workers Great Lakes Mobilization, 1982. Courtesy Labadie Collection, University of Michigan

Earlier this month, I got to spend some time with the Joseph A. Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan. The Labadie Collection is one of the oldest and most comprehensive collections of materials related to anarchism, anti-colonialist, antiwar, civil rights, labor, feminism, LGBTQ, and other movements. Named after Detroit labor organizer and anarchist Jo Labadie, the collection began with a donation of books, pamphlets, newspapers, and memorabilia from his personal library in 1911.

I began on the web portal, searching for arts-related terms like graffiti, fine art, dance, theater, and more. From there, I requested files from anything that seemed relevant. Inside the library’s special collections research room, I spent about two hours with the items I selected, brought to me in two large boxes filled with file folders.

Here are a few highlights:

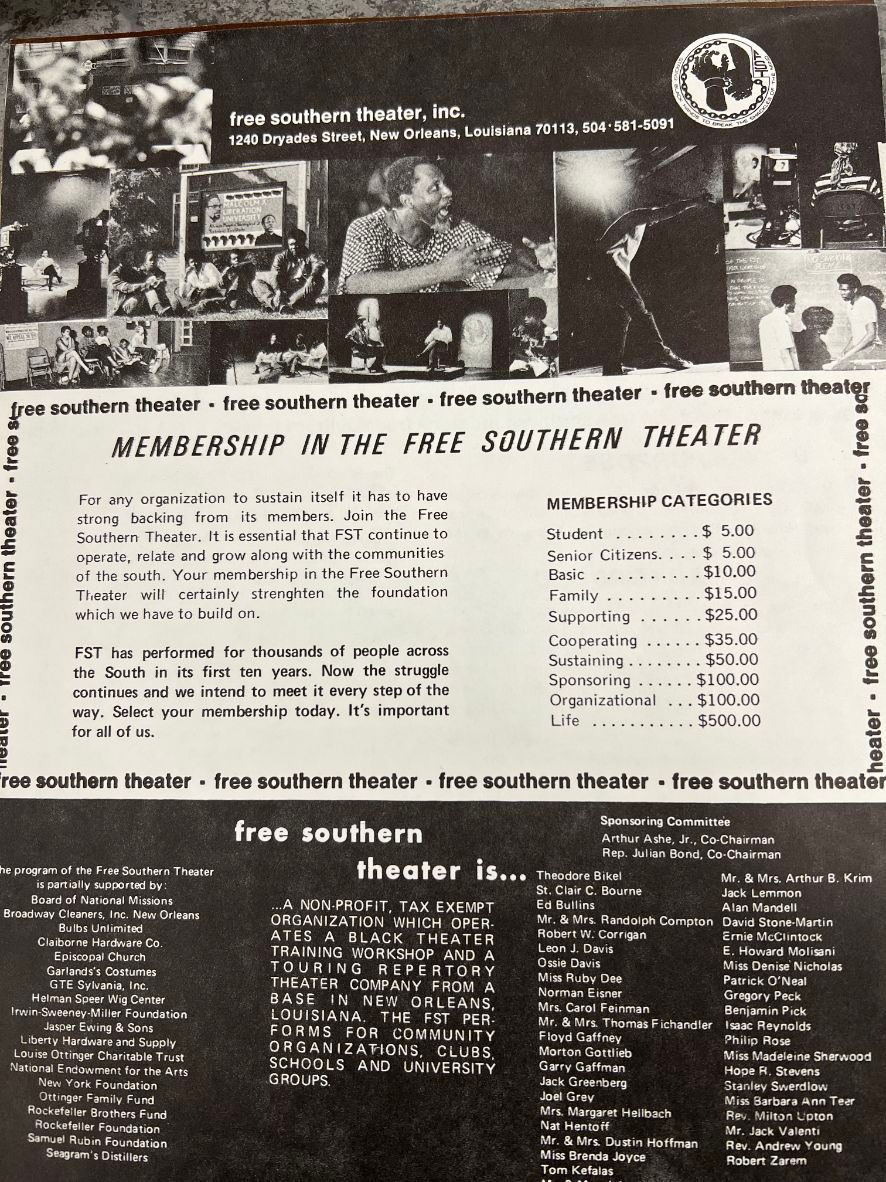

Free Southern Theater

Founded in 1963 by Doris Derby, John O’Neal, and Gilbert Moses at Tougaloo College, the Free Southern Theater (FST) staged plays that combined art and social awareness for Black audiences.

Much of the group’s work centered on the experiences of poor, Black southerners and performances were held in Freedom schools, churches, and outdoor stages. The FST provided free admission to revolutionary plays and community workshops, garnering financial support from beneficiaries such as Langston Hughes and Harry Belafonte.

The Labadie Collection included programs, fundraising letters, reviews, and action plans for increasing the reach of the nonprofit. In a prospectus for the organization, the founders argued that in Mississippi, cultural resources available to the Black community were “virtually nonexistent” at the time.

Membership drive from Free Southern Theater in the Labadie Collection.

They also shared their plans to create the theater: “We will work toward the establishment of permanent stock and repertory companies, with mobile touring units, in major population centers throughout the South, staging plays that reflect the struggles of the American Negro and, in time, integrated audiences.”

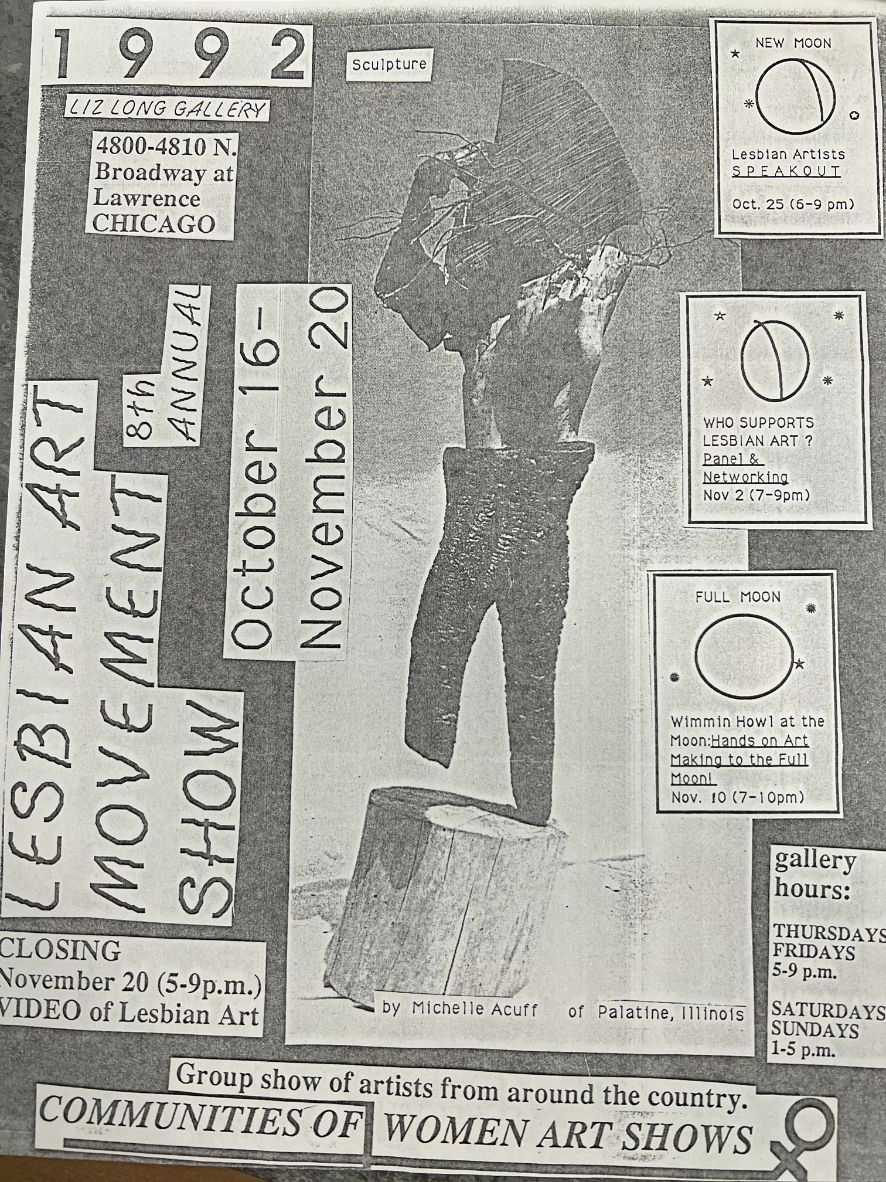

Gay liberation art

A folder labeled “sexual freedom - gay liberation - art” included calls for artist submissions, invitations to openings, and press releases. Many items were from the 1990s in New York, but the folder also included events in Chicago and Toronto.

One flyer advertised an art event sponsored by Clit Club, a New York based nightclub and performance venue conceived by artist-activists Julie Tolentino and Jocelyn Taylor in 1990. The queer, sex-positive lesbian club ran until 2002.(There are few photographs of the actual parties because of a no-camera policy instituted to enhance the club’s intimacy and designation as a safe space.)

Another press release from an art opening featuring young lesbian and gay artists in 1991 reads like an artist call from today: “In the midst of current attacks on artistic expression and the onslaught of anti-lesbian and gay prejudice, many brave, young visual artists are paving the road for the future — standing proud and queer.”

A flyer advertising a 1992 show featuring lesbian artists in Chicago in the Labadie Collection.

Radical art

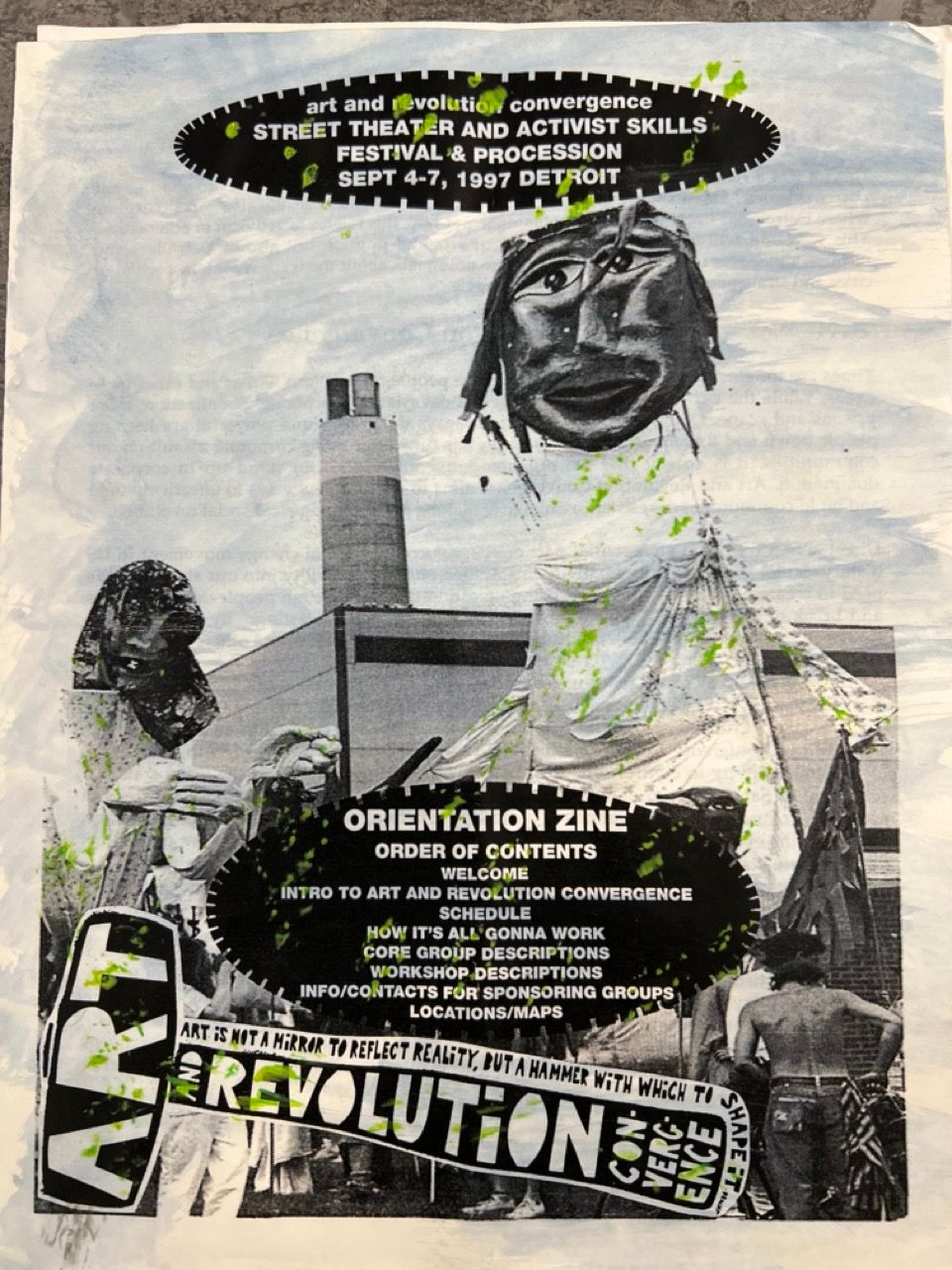

A flyer from a 1997 Detroit festival called “Art and Revolution Convergence” caught my eye. A street theater and direct action festival, the event featured several days of workshops on activism and movement building through dance, puppetry, and music.

According to the event's zine, the festival was conceptualized in Chicago in 1996 during the Democratic National Convention. A group of artists and organizers from San Francisco and Chicago sponsored a week-long theater workshop during a conference of 700 anarchist and radical activists.

When some artist-organizers returned to San Francisco, they worked with community groups and unions on numerous actions and demonstrations, “helping to get visibility, media coverage, and make the events more inspiring to both participants and observers.”

Here’s a quote on the front page of the zine from German playwright and poet, Bertolt Brecht, that will stick with me: “Art is not a mirror to reflect reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.”

Art and Revolution Convergence Zine from 1997 in the Labadie Collection.

I’m not sure about the organizers behind a pink “Yes, Art Is Shit!” flyer from the collection, but it references the 1974 Ann Arbor Art Fair, which according to the flyer, was expected to gross $1 million that year. I’ll just let some of the text from the flyer speak for itself:

“There is one fundamental reason why today’s Art is produced — because it brings a top dollar from consumers and collectors in the marketplace. There is nothing essentially different from the street extravaganza here, and a well-stocked K-Mart. Each has merchandise for sale, one amid cash registers and shopping carts, the other surrounded by Art aficionados and high price tags. The producers of Art are like most of us — selling their time and labor in order to live. As long as relations among people in society revolve around economic survival, Art will be indistinguishable from any other commodity, and we will be encouraged to buy, sell, invest in, and contemplate Art. When we as producers take direct control over all aspects of our lives, Art will be inseparable from life, just as play and work will merge and be one.”

complete our survey on arts media

Graffiti

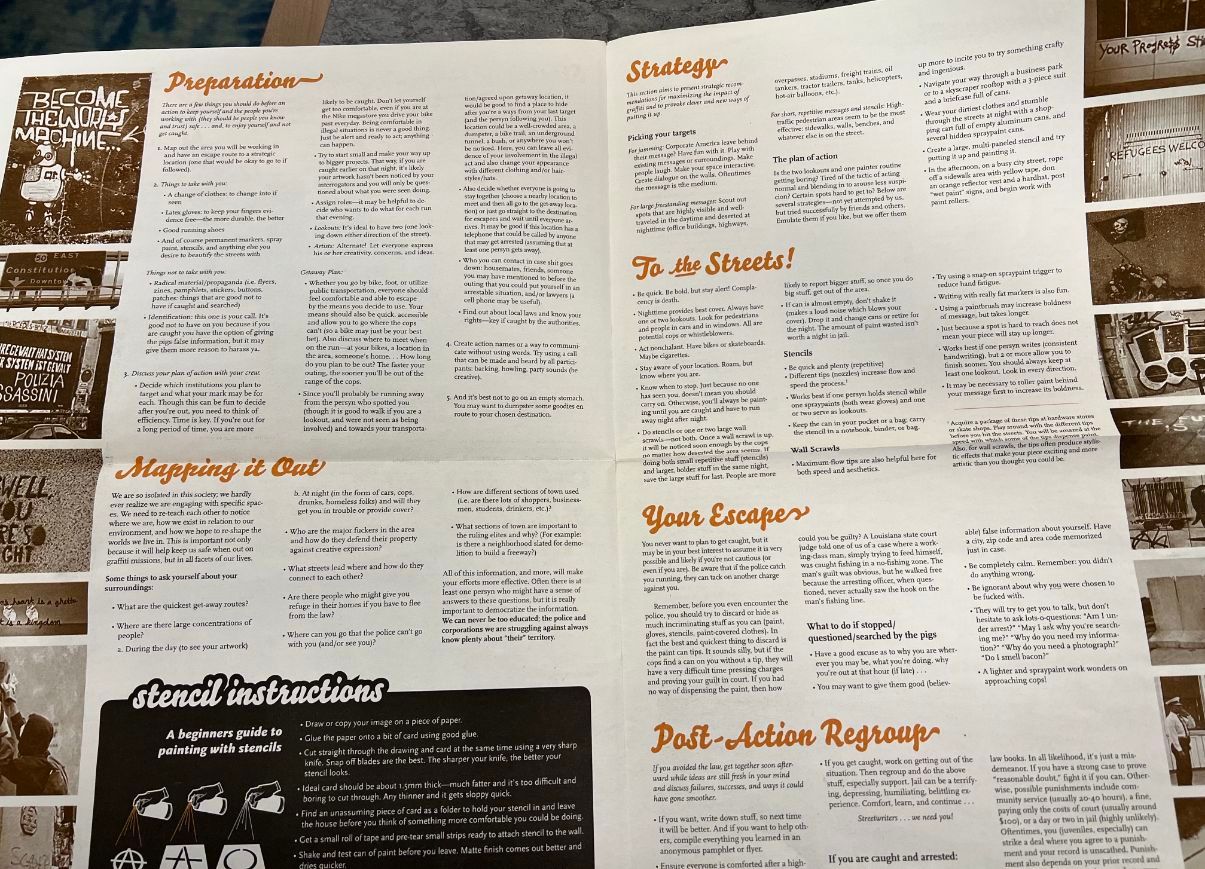

A how-to graffiti guide, “for those who scheme and those who dream” was created in spring 2002 by the anarchist group CrimethInc. More than 4,000 copies of the zine, “The Walls Are Alive,” were published and distributed. CrimethInc describes itself as a “rebel alliance — a decentralized network pledged to anonymous collective action — a breakout from the prisons of our age.”

The guide includes practical tips for getting started as a graffiti artist including having a getaway plan, using a snap-on spraypaint trigger to reduce hand fatigue, and not taking radical material or identification. (“It’s good not to have on you, because if you are caught you have the option of giving the pigs false information, but it may give them more reason to harass ya.")

CrimethInc's The Walls Are Alive zine and how-to graffiti guide in the Labadie Collection.

Resistance Records

I was definitely surprised by the inclusion of racist materials in the collection. I skimmed through one folder dedicated to Resistance Records, the racist, white power music label founded in Windsor, Ontario in 1993 and previously based in Michigan.

The folder included letters to supporters (one began “Dear white racial comrade: Racial Greetings") and a retail price list for CD and cassette releases including “Aryan/New Storm Rising” and “Nordic Thunder/ Born to Hate,” listed for $9.88 and $14.88, respectively.

I asked the curator for the Labadie Collection, Julie Herrada, about the inclusion of racist materials when the vast majority of everything else skews progressive.

“Past curators have included some right wing and racist materials in the past by mandate from the library director,” she told me via email, “but this is a small fraction of the content we hold. It is not a current collecting area for us, however it is sometimes relevant to the research that is done here.”

Protest records

To cleanse the newsletter a bit, I’m including an advertisement for Rounder Records’ protest catalogue. Rounder Records is an Americana and bluegrass record label based in Nashville.

A flyer from the collection introduced me to even more artist-activists, including Aunt Molly Jackson, a folksinger and union organizer from the coal-fields of Kentucky, The Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band and the New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Band, which are among the first feminist rock and roll ensembles in the U.S., and Hazel Dickens, the late bluegrass singer-songwriter and advocate for coal miners who wrote pro-union, feminist songs.

I wish I had more time with the collection, but my two hours left me feeling even more inspired about the importance of artists in social movements. It was interesting seeing the connections and similarities between movements past and present. I also left with ideas for stories and new points of exploration.

Check out the collection

The Labadie Collection is open to students, visiting researchers, and members of the community. You can also find political posters from the collection — on anarchism, civil liberties, feminism, labor, and other political movements — online.

Welcome, Rebecca!

Through my visiting fellowship with the Center for Racial Justice at the Ford School, I’ve been working closely with Rebecca Hagos, a master’s student in public policy. As my graduate research assistant, Rebecca has been helping me develop a social media strategy for this project, and think through some bigger ideas I plan to execute in 2023. We’re cooking up some cool new projects together and I’m super grateful for her help.

Support the art rebellion

As usual, please consider forwarding the newsletter to a friend. If you enjoyed any of the history in this newsletter, be sure to follow the art rebellion on Instagram where we occasionally post #artactivismhistory. And if you have questions about the Labadie collection or anything else, just reply to this email!

As I near the one year mark of launching this newsletter, I want to thank everyone for following along this journey with me. I appreciate each and every person who takes the time to open and read my work. It really means the world.

Happy New Year, y’all.

Our mailing address:

620 Oxford Rd

Ann Arbor, MI 48104

Copyright © 2022 the art rebellion, All rights reserved.