On getting immersed into Ann Arbor's art scene

Since moving to Ann Arbor a few months ago, I’ve experienced a ton of great art.

Since moving to Ann Arbor a few months ago, I’ve experienced a ton of great art.

The wonderful world of art in Ann Arbor

By Makeda Easter

Happy Halloween! Being in Ann Arbor the past couple months has gotten me even more into the spooky spirit. There’s a chill in the air, and the entire city is lined with resplendent trees — their leaves exploding in various shades of reds, yellows, and oranges. Many of the homes in my neighborhood are decorated with pumpkins, some half-eaten by plump squirrels that seem to completely run this town. It’s safe to say this is the most “fall” fall I’ve ever experienced.

Since moving to Ann Arbor in August, I’ve also experienced quite a bit of art. And so I wanted to dedicate this month’s newsletter to sharing the wide variety of shows and performances I’ve enjoyed.

Just a few days ago, I attended “Sound and Resistance,” a virtual event hosted by Allied Media Projects, a network of groups rooted in Detroit. The hour-long show featured a panel discussion and pre-recorded performances by music artists who are also organizers. Artist Sophiyah Elizabeth described her work, “The Green Room: Earth Noire,” as a sonic exhibition exploring intersections between human and plant life. Tazeen and LuFuki, a guitarist, vocalist, composer duo, who also co-direct the Detroit chapter of Gathering All Muslim Artists, shared a meditative piece in an outdoor, backyard setting. And Chicago-based Damon Williams, an organizer and hip hop performer, showed several pieces celebrating freedom and liberation.

A screenshot of the Allied Media Projects' Sound and Resistance virtual event. Duo Tazeen and LuFuki perform their work Meditation on G.

As part of the Knight Wallace Fellowship, I’m auditing several classes at the University of Michigan. Even though I’ve written about arts and culture for the past six years, I’ve never taken an actual art history class, and so I was excited to enroll in an undergraduate course focused on global arts and resistance.

During one class, we spent time at the Stamps Gallery, which is part of the university’s School of Art & Design. In August, the gallery debuted Act III of photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier’s “Flint Is Family In Three Acts.” The multipart exhibition, also concurrently being shown at the Flint Institute of Arts and the Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, is the culmination of Frazier’s five years working with Shea Cobb and Amber Hasan, both artists, activists, mothers, and residents of Flint, Michigan.

A 2019 photo from LaToya Ruby Frazier's Act III in Flint. The description reads, Zion Taking Her First Sip of Water from the Atmospheric Water Generator with Her Mother Shea Cobb.

The work stems from Frazier’s five month visit to Flint in 2016 to document three generations of women coping with the devastating water crisis in their hometown. Act III includes photos, video, and text from Frazier’s return to Flint in 2019 and 2020. Frazier documented Hasan’s work to bring an Atmospheric Water Generator to the north side of Flint, which provided clean, safe, and affordable drinking water to residents.

A 2019 photo from LaToya Ruby Frazier's Act III. The description reads, A Flint Community Member Holding Her Water Jugs at the Atmospheric Water Generator on North Saginaw Street.

“No matter how dark a situation may be, a camera can extract the light and turn a negative into a positive,” reads a quote from Frazier on the gallery wall. “In creating ‘Flint Is Family In Three Acts,’ I see the role of photographs as empowering and enacting visible change.”

I also visited the University of Michigan Museum of Art with the same class. We spent about an hour and a half in the “Watershed” exhibition, which featured 15 artists with recent work exploring issues facing the Great Lakes region and its future. “Watershed” emphasized Black and Indigenous artists and the relationships marginalized communities have to water in the area.

A few of the works in the show included “The Gift,” a 40-foot mural from artist Bonnie Devine which calls attention to the devastating effects of colonial expansion across the Great Lakes watershed — the removal of Anishinaabe people from the region, and their erasure from historical narratives. Pope.L’s “Flint Water Project” was originally staged in 2017 as a performance event in Detroit. The artist set up a store that sold bottles of water contaminated with lead and E.Coli from the home of a Flint resident, with proceeds donated to the United Way of Genesee County and Hydrate Detroit.

UMMA presented a smaller version of the original store.

Cai Guo-Qiang’s gunpowder on canvas 2018 work, “Cuyahoga River Lightning,” reminds viewers of an environmental disaster that happened over fifty years ago — when a section of the Cuyahoga River that runs through Cleveland caught fire after more than a century of pollution from the oil, steel, and sewage industries.

UMMA, which is also a popular study spot on campus, partnered with local organizations and artists to transform its space into an election hub for students and residents. As we head into the U.S. midterm elections, the museum is a place where people can register to vote, get a ballot, and access other voting resources.

The University of Michigan Museum of Art has become a voting hub on campus as the U.S. midterm elections approach.

Walking through the Diag, a central gathering spot on campus, I encountered Tatyana Fazlalizadeh’s public mural installation, “To Be Heard.” The Brooklyn-based artist and activist was commissioned by the university’s Institute for the Humanities to amplify voices of marginalized groups at the University of Michigan.

In September, Fazlalizadeh spent several weeks with Black and brown, queer, and women-identifying students to understand their experiences at the university. One Black and white cutout of a student wearing a t-shirt with large block letters reading, “Do not let this school break you down,” caught the attention of those making their way to and from classes. (University of Michigan’s undergraduate student population is only 4% Black).

I’m grateful to have experienced live performances this month as well.

Years ago, I was enthralled by the 2011 documentary dance film “Pina,” celebrating the electric work of the late German choreographer Pina Bausch. Recently, I saw “The Rite of Spring” at the university’s Power Center. Choreographed in 1975, the work is driven by the question,“how would you dance if you knew you were going to die?”

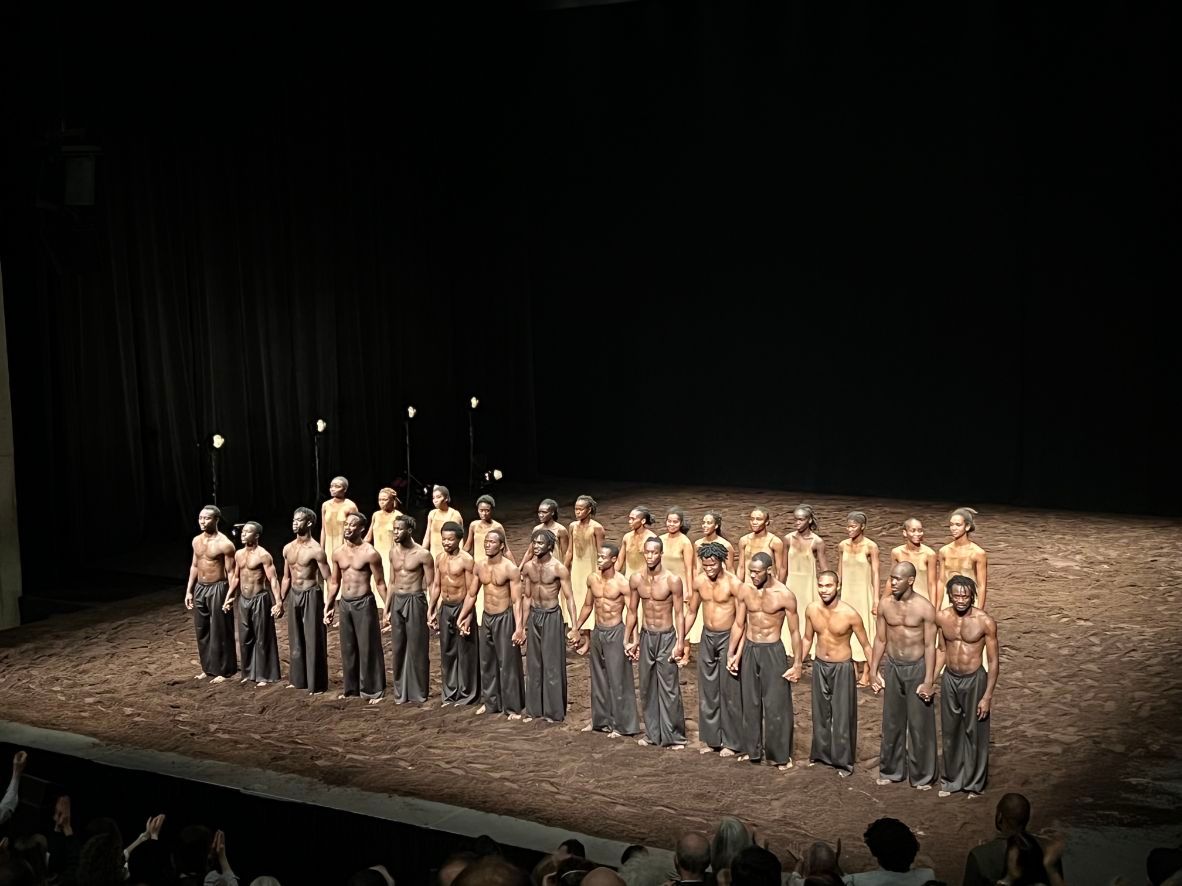

A co-production between the Pina Bausch Foundation, École des Sables, a center for traditional and contemporary African dance in Senegal, and Sadler’s Wells in London, the performance represented only the fourth time that any group of dancers outside of Baush’s home company Tanztheater Wuppertal danced “Rite of Spring.” And this was the first time the work was performed by dancers from African countries.

Dancers from The Rite of Spring performance at the Power Center received a standing ovation.

According to program notes, more than 200 dancers submitted video auditions to two former dancers with Tanztheater Wuppertal, who led staging of the work.

137 dancers were then invited to learn excerpts from the choreography at workshops in Burkina Faso, Senegal, and the Ivory Coast. From there, 38 dancers from 14 countries became part of the final cast.

“These dancers will do what all dancers do; they will interpret the movement of Pina Bausch. The dance is always the same, but depending on what area you live in, there are different energies,” said Germaine Acogny, co-founder of École des Sables,

Simply put, the performance was phenomenal, and I was on the edge of my seat the entire time. An astoundingly physical work, I was in total awe of the dancers who ran at full speed, throwing their bodies to the ground or sometimes on top of their dance partners. (Read a review in the Guardian here).

In mid-October, I attended a performance of Wynton Marsalis’s 1999 work, “All Rise (Symphony No. 1).” A collaboration between Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra and the university’s symphony orchestra and choir, more than 200 artists filled the stage.

The score was luxurious, drawing from the sounds of gospel, blues, country fiddling, New Orleans parade music, Argentine tango, and other influences. I appreciated Marsalis’s detailed program notes, which walk through inspiration behind each of the work’s 12 movements and include technical cues on the harmonic direction and flow.

Hundreds of musicians filled the stage for Wynton Marsalis's All Rise (Symphony No. 1), performed at the University of Michigan's Hill Auditorium.

Here are some of his vivid notes about an after-intermission song, “Saturday Night Slow Drag.” “The slow blues: unsentimental romance, wise love, a dance, an attitude, a modality. The slow drag: vertical expression of the most salacious horizontal aspirations. Saturday night: when things that should be confessed on Sunday take place.” So vivid, right?

In addition to these shows, I’ve been doing my best to meet with curators, artists, and arts administrators to better understand the landscape across Michigan. My goal over my next six months in Ann Arbor is to immerse myself even further in the arts and to collaborate with some groups in the region.

Have you seen any interesting art? Hit reply, and let me know what work has inspired you lately.

Support the art rebellion

We are so close to 300 subscribers! Please help us get there by forwarding the newsletter to a friend and asking them to sign up. And don’t forget to follow us on Instagram.

Thanks as always for reading, and see y’all next month!

Our mailing address:

620 Oxford Rd

Ann Arbor, MI 48104

Copyright © 2022 the art rebellion, All rights reserved.