How an Omaha art space is shaping the future of the city's scene

Brigitte McQueen launched the Union for Contemporary Art in 2011. Over 13 years, it's become an inclusive and welcoming space for local artists, and has left a lasting impact on Omaha.

The Union for Contemporary Art, a nonprofit dedicated to giving everyone access to creative culture, lives in an unassuming North Omaha neighborhood.

It sits at the corner of 24th and Lake Street in an active culturally emerging district, with similar organizations including the Great Plains Black History Museum, the headquarters for the Omaha Star newspaper, and the Dreamland Plaza with the Jazz Trio sculpture memorializing North Omaha’s musical history.

At only 13 years old, the organization has become a staple in Omaha’s small art scene, helping dozens of local artists thrive and filling a much-needed gap for community-driven and inclusive art.

Inside the Union for Contemporary Art. The nonprofit has a fiber studio, library, and other spaces for artists to hang out and create work. Photos by FinesseMedia

It’s not too surprising that the spark for the Union began within another arts center.

On a frigid December day in 2010, Brigitte McQueen was ending her last week as an employee at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, a residency and exhibition space in downtown Omaha.

McQueen was working in the Underground, a space she converted from an old and dilapidated brick basement into an exhibition room highlighting work from local artists. Suddenly, a pipe burst and “totally destroyed what I had built down there, which I still hold as a very interesting kismet moment in my life,” she says.

McQueen says she witnessed a lack of interest and support for contemporary artists from the handful of Omaha art institutions like Bemis Center and Joslyn Art Museum. Most exhibitions focused on what national and international artists were doing, catering toward an audience that already had a background and was knowledgeable in art. And some say the wider arts community in Omaha has engaged in unsavory, clique-ish and exclusionary behavior.

McQueen knew a change was needed.

One recent example is the disbandment of a group called Arts Omaha. Originally founded as a social club, it transformed into an informal fundraising organization that excluded organizations with budgets with less than $2 million in funding, with the oblique impact of hurting organizations run and serving people of color. It later disbanded after McQueen wrote an essay about white supremacy in Omaha’s cultural sector and her experience with the group.

Running the Bemis Underground for a year exposed McQueen to the kind of support local artists truly needed, while also considering how segregated Omaha was and still is.

Just a month after the pipe burst, McQueen founded the Union, an art-focused organization with an exhibition and theater space serving the primarily Black residents in North Omaha, and Omaha artists at any stage of their development.

At the time, Omaha’s two major visual arts organizations were downtown with a handful of galleries and smaller museums sprinkled across the rest of the city, like South Omaha’s El Museo Latino, a museum dedicated to the Latino arts of the Americas, but leaving very little in terms of a museum experience in North Omaha.

The Union aims to close that gap, through its exhibitions, public studios, classes, community garden, and theater. It also offers grants, fellowships, and residencies to marginalized people in Omaha.

Omaha, Nebraska’s largest city of nearly 500,000 has historically, and continues to be very segregated. According to a demographic study from the University of Nebraska Omaha, North Omaha is primarily a Black neighborhood, with 43% of the residents being African-American. In South Omaha 44% of its residents are Hispanic or Latino. And in Douglas County, where Omaha and its suburbs are primary within, 78% of residents are white.

“The Union was born of those two things,” McQueen says, “wanting to to address the segregation that exists in Omaha, to create a space for myself and people like me, and to figure out ways to better support our local art community so that we would stop losing artists because at the time, we were losing them in droves.”

McQueen launched the Union a few blocks south from its current location, in a vacant former food bank by Catholic Charities of Omaha. About a month in, Brigitte had a volunteer day where about 100 people helped her paint and clean the space.

“When I started the Union, I had only been working in the nonprofit sector for less than a year,” McQueen says. “I didn't know anything about being an executive director or starting a nonprofit. I didn't know a lot about a lot of things. And so I think those first couple years really were focused on me teaching myself how to start and run a nonprofit. I was the only employee at the Union for the first three years.”

In 2012, McQueen launched the fellowship program, converting five office spaces into studios for local artists, and began curating exhibitions in storefronts in North Omaha since there wasn’t space in the former building to host exhibitions.

Curating exhibitions — discovering artists and sharing their work with the community is sacred to McQueen. She doesn’t have academic training in art, and during her early days working in the arts, “many other curators in Omaha pointed that out to me and refused to let me own that title, or acknowledge that the work that I was doing was curatorial.”

She now sees her nontraditional background as a strength.

“It allows me to be able to create conversations with anyone who walks off the street, about what they're seeing and experiencing,” McQueen says. “If that means we just stand there and talk about how much you like that color pink, then we're gonna stand there and talk about how much you love that color pink, and how it's making you feel, and how it's moving you.”

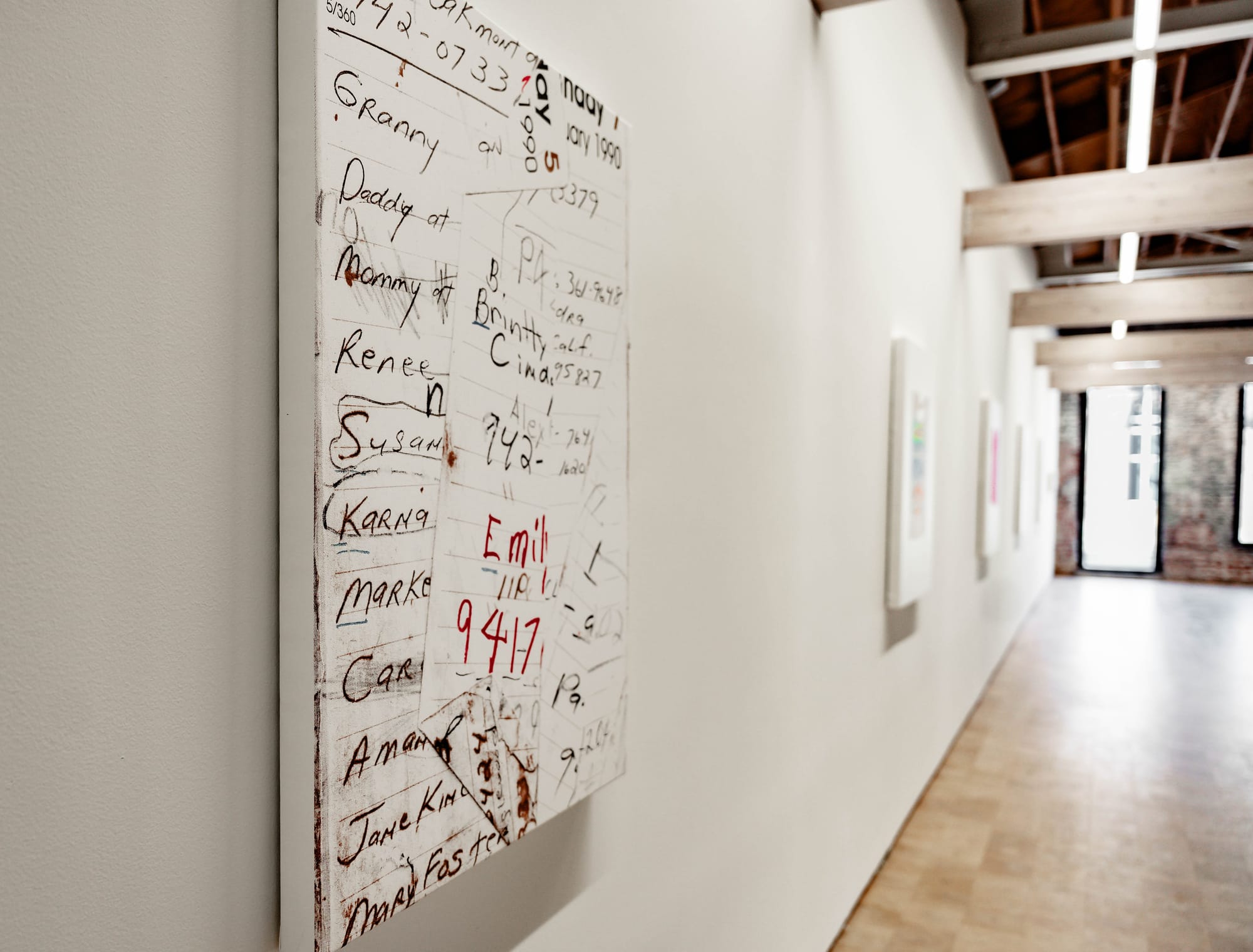

The Union's Wanda D. Ewing Gallery promotes the work of local and national artists. Currently on view is an exhibition by artist Leslie Diuguid analyzing thrifted artifacts that act as a material memory. Photos by FinesseMedia

Over time, the Union’s budget grew from an initial $60,000 donation from the Weitz Family Foundation in 2011 to over $2 million, expanding to what it is today. The organization has also successfully completed two capital campaigns, raising just over $5 million to renovate its current home, and over $8 million to build a theater.

In the past decade, the Union has hosted thousands of visitors in their Wanda D. Ewing Gallery, art studios and performing arts spaces. It’s awarded 20 artists fellowships which come with a free private studio, a $3,000 honorarium, $500 professional development funds, a one year pass to their co-operative studio, and opportunities to engage with other arts and culture workers.

Since 2020, they’ve also disbursed $312,000 in grants to more than 200 artists throughout the Omaha-Lincoln area, through the Populus Fund program, which is supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

On a hot summer day in 2019, I visited the Union with my sister. To get there, we drove from South Omaha, passing through Downtown to get to the space in North Omaha.

After checking in at the front desk, we walked into Angela Drakeford’s “Homecoming,” an installation that resembled a domestic interior space that people were welcome to engage and sit in. There was no pretension of what the exhibition was, and no rush to get in and out. Visitors were allowed to breathe and sit down and ponder.

While immersed in the show, we both saw a woman sitting and sewing a quilt, and we ended up sharing space with her.

The woman is Celeste Butler, an artist working in Omaha who is one of the many the Union has helped in establishing a fruitful career in the arts.

A fiber artist with a deep history in Omaha, Butler was highly influenced by her mother, who she calls a “Renaissance Woman”, referring to the two burgeoning Chicago and Harlem Renaissances.

Growing up in North Omaha, Butler experienced firsthand the impact of segregation in the city, but also the cultural richness particular to life in that neighborhood. She recalls it being almost like a Garden of Eden, being able to reach out a hand from a window in her childhood home and to pluck a fruit from a tree.

Butler remembers being inspired by the intimacy of quiltmaking, using it as a starting point in her practice.

Recalling her childhood, she says, “the quilts that hung on the line, all the colors, the smell of the laundry; when I used to see those quilts just blowing in the wind, they were just majestic. That was the fiber of the neighborhood.”

The support the Union offered to Butler kept her pushing to maintain a career as an artist through two fellowships.

“My support from the Union has been epic. Even now in my practice, if I'm stuck in something, I can walk right through those doors and say, ‘hey, can you help me with this?’” Butler says. “I've received that level of love and support which made me feel at home and it made me want to dig deeper.”

Her quilts are visual testaments to this care and experience, and they are currently being exhibited at the Bemis Center in an exhibition titled “Neo-Custodians: Woven Narratives of Heritage, Cultural Memory, and Belonging.”

“Omaha can crush you because it is not vibrant like other places, especially when it comes to the arts, and it can be stifling. It can almost snuff out and pull the life out of you and make you want to stop and go out and get a regular job. I never got that feeling with the Union.”

McQueen also acknowledges the challenges of being a working artist in Omaha and running an arts space in the city. Omaha doesn’t have a thriving gallery culture, which often attracts artists and encourages them to stay.

“I do feel like the work that we do here has deeply benefited and supported the creative practice of countless artists, and I'm so proud of that,” McQueen says. “But I'm also aware it exists in a space that is not always conducive to a greater support of creatives.”

Another artist in Omaha maintaining a presence through the Union’s support is Andrew Johnson, who is self-taught. He has exhibited two times at the Union, most recently in a 2023 show titled “Sanctuary.”

Like many artists, Johnson maintains a career outside of his art practice. A structural engineer, his artistic work, particularly his earlier pieces, are defined by his relationship to mathematics and science.

“I don't know if there's been anything like the Union. Brigitte gives people like me, like Celeste, opportunities to have an audience, which is huge. They've done a tremendous job, more so than any other organization in town for almost anything. You don't ask anything in return.”

After over a decade of supporting the arts in Omaha, McQueen will be stepping down as the executive director of the Union in the spring of this year.

“As a founder, I have a responsibility to step away,” she says. “I feel like it is a detriment to an organization if a founder stays for too long.”

In this period of transition, McQueen is ensuring “that my team is cared for. I want to make sure that the organization is cared for and that our stakeholders feel cared for.”

She’s not totally sure what the future of the Union will look like, but she’s hopeful, “that this work continues long, long, long after I'm gone, and that it continues to thrive and make beautiful things happen for our community.”

Jonathan Orozco is an artist and art historian in Omaha, Nebraska, where he has lived for the majority of his life. He earned a BA in art history from the University of Nebraska Omaha in 2020 focusing on contemporary painting and fashion. He regularly contributes to local and national art publications on the Omaha-Lincoln art scene, like in White Hot Magazine, Artillery Magazine, Omaha Magazine, and The Reader.